Sentence fragments: Not such a big deal after all

I have often heard--usually as evidence of a general decline in literacy--that your average newspaper or magazine is written at a seventh-grade reading level. But when bandying about phrases like "a seventh-grade reading level," we are seldom prepared to explain what features we're talking about. The most obvious, go-to guess is probably vocabulary, but I think something else is at work. After all, the vocabulary of newspapers and magazines does not suffer from any shortage of multi-syllabic, Latinate abstractions.

I'm willing to bet that the "seventh-grade" metric has more to do with sentence length. When we say "seventh-grade reading level," what we may mean is not that newspapers and magazines have "dumbed down" their vocabulary, but that they enforce fairly strict limits on the length of their sentences. They have likely discovered that such limits will make their articles more widely read--an important consideration for writers. That these limits may resemble seventh-grade texts is likely more of a coincidence than a compromise of values.

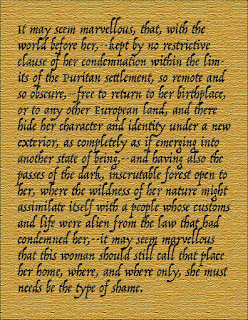

This may explain why students have such a terrible time with 19th century Romantic prose of the sort that's caused much anguish in Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter--a powerful, beautiful, and beleaguered novel that might enjoy a little more love if its sentences weren't so damn long (click on the image to enlarge):

Now clearly this passage presents some vocabulary challenges, particularly in Hawthorne's use of words our students may think they already know: marvellous, character, type. But a student could look up and learn every challenging vocabulary word in this passage (11, by my count) and still struggle to understand it, simply because of its length. The idea expressed in the sentence is simple enough: that it's strange the disgraced Hester would stay in Boston when there are so many alternatives available to her where she doesn't have to live in shame. But this 127-word collosus puts you on hold right away, requiring you to keep the opening in mind as Hawthorne leads you through so numerous a series of parenthetical free modifiers that he feels compelled to begin the sentence anew--to remind the reader where he began--before finally consummating the deal with the necessary subject and verb.

I have heard 11th and 12th graders read much shorter sentences aloud, and (if their voices accurately represent the level of their focus and comprehension) give away the exact moment when they are no longer making meaning, but simply decoding words aloud. So when we talk about sentence length, we may be describing the level of sustained attention that a given sentence demands. Perhaps, in this era of ubiquitous texts to be read, it's not a lack of literacy we're suffering from, but attention.

This idea struck me a few weeks ago while reading the article Embracing My Gray Hair, Possibly for Good, in Time magazine, by Sally Susman, a corporate executive who is nearing 60. Susman, like people everywhere during the COVID-19 shelter-in-place, has had to survive without the aid of her hair stylist, forced to watch the gray she would otherwise have colored out taking over her hair. After describing her lifetime relationship with her locks, she comes to this realization:

"Today, my relationship with the gray orb atop my head is different. I'm not worrying about fashion or social norms. Maybe going gray is a symbol--a demarcation of my life before and after. My new appearance forged in the sorrow and the pain of the pandemic. A daily reminder of my 91-year-old mother-in-law's struggle to survive in a senior center rampant with the disease, of my young adult daughter's forced return home from graduate school when her university shuttered. And of my cousin's anguish at having to close the restaurants he spent his life building. The silver streaks on my head keeping those losses top of mind, literally."

Now, you may have noticed that this is a paragraph composed almost entirely of sentence fragments, but probably not. Once the third sentence is completed, Susman follows up with two successive noun phrase appositives (the legendary Smack-Talker, the second one stretched out further with an additional prepositional phrase), a stand-alone prepositional phrase, and an absolute phrase (or a "Wannabe Sentence"), each acting as if it were a complete sentence--even though as phrases, they should be punctuated with commas.

But if she had connected the phrases with commas--as an 89-word Hawthornian extravaganza--she might have put off the reader. Perhaps these fragments (what some call stylistic, but which might better be understood as pre-emptive) are the results of an editor's insistence that the sentence not go all Hawthorne on the reader, a compromise which would confirm what I'm suggesting about attention being the difference-maker.

As an English teacher, I noticed the sentence fragments, but does it really matter? As a reader, I didn't miss those comma-tails at all. I just enjoyed the writing. Ultimately Susman shows us that it's not the punctuation that makes the passage worth reading, but what's between the punctuation. If a student of mine were to write a paragraph like that, I would not begrudge the fragments, but celebrate the students' impulse to stretching out his or her sentences.

Comments

Post a Comment