What's Going On? Sentence Instruction In a Time of Crisis

One of the challenges of writing a blog devoted to a specialized topic like teaching sentence love is that it can sometimes seem tone deaf to the problems of the world, which are at the moment, very real and desperate. In other words, when people like George Floyd are murdered by police--yes, black lives matter--and our republic seems on the brink of disintegration with no leadership willing or able to make an effective case for unity and healing, it seems rather callous, dare I say privileged, to write publicly about anything else.

Another way of looking at it is that if I were in school right now, I'd want my students to think and talk and write about, as Marvin Gaye asked so beautifully, "What's going on?" But even that presents a professional problem, rooted in the difference between my privilege, relative to the experience of my students, who are overwhelmingly students of color. At times like this, it seems best to listen and learn rather than attempt to teach. And if venting is what they need, whether out loud or in writing, I must recognize this and allow for it before I attempt to do anything else.

But once the venting is done, how can I return to my job of writing instruction in a way that acknowledges the reality of my students' perspective? I begin by reminding myself that learning how to control and eventually channel our anger is one of the great problems of life, and that the ability to write clearly and powerfully about things that anger you is a worthy challenge in any writing class.

Is there even a place for sentence instruction here? I think the answer is yes, if you focus not on correctness and mastery, but on helping to develop your students' voices when they need it most, so that they might focus and channel their emotion effectively.

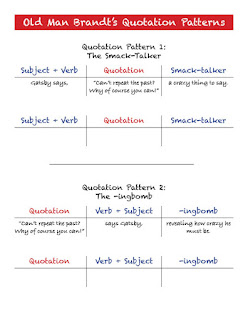

I'm thinking specifically of the quotation patterns I make use of in the classroom:

I use these two patterns to help my students navigate their way clearly through quotations, a skill that is challenging to them. Oftentimes they mangle quotations by employing the quote itself as the subject of the sentence: "Can't repeat the past? Why of course you can" was a quote said by Gatsby. The quotation patterns offer a way out of this problem of execution by focusing not on the quote, but on the speaker as the subject of the sentence.

But for our purposes here, the most important feature of the quotation patterns is the free modifier at the end of each--a Smack-Talker in Pattern 1, and an -ingbomb in Pattern 2. These additions are important not simply because they make the sentence longer, but because they are generative--that is, they produce the need for further comment, helping the students to handle that dreaded question, "What do I say next?"

Here is a pair of statements on the protests over the murder of George Floyd, the first from the current occupant of the White House, the second from the former:

"You've got to arrest people, you have to track people, you have to put them in jail for 10 years and you'll never see this stuff again."

"The overwhelming majority of participants have been peaceful, courageous, responsible, and inspiring. They deserve our respect and support, not condemnation."

If I were in class today, I would have my students choose one of these statements and write it up in a quotation pattern. Hopefully, with a little work, students might produce some sentences like this:

Donald Trump says, "You've got to arrest people, you have to track people, you have to put them in jail for 10 years and you'll never see this stuff again," a statement that I disagree with.

"The overwhelming majority of participants have been peaceful, courageous, responsible, and inspiring. They deserve our respect and support, not condemnation," says Barack Obama, showing the kind of leadership we need during a time of crisis.

Once the students have written a serviceable quotation pattern, I would then have them use it as the opening sentence of a journal entry. If they finish a Pattern 1 with something like "a terrible thing to say," I would expect them to explain what they consider terrible about it: what do you mean by that? You're not saying you support violence, are you? What do you mean by terrible? Can you explore that further? The same process would apply if the student wrote a Pattern 2: what do you mean by leadership? Are you suggesting that Trump is not showing leadership?

The goal here is not to write a perfect quotation pattern, but to use it to frame a response that balances thought and emotion, channeling the students' feelings toward a deeper understanding than they originally started with. There is the odd chance that I'll get a Trump supporter--although they're a particularly rare bird in my school--and I would allow that student his or her political opinion without penalty, however much I may oppose it.

"Opinions are bad for business," says the storekeeper in Inherit the Wind, when asked for his view on the Theory of Evolution. But the freedom to express opinions is necessary to both democracy and justice. There are times when business will have to suffer. So I'll close by offering once again an opinion that may lose me some readers: black lives matter, and the success of American democracy depends on whether we are willing to recognize that.

Marty, this is brilliant. All of it, but I especially was caught by your statement, "the ability to write clearly and powerfully about things that anger you is a worthy challenge in any writing class."

ReplyDelete